A Day of Unity that Must Live On

By Khin Ohmar • August 9, 2010Khin Ohmar took part in the 1988 pro-democracy uprising as a university student in All Burma Students Democratic Movement Organization (Ma-Ka-Da) in Rangoon. She is now the coordinator of Burma partnership and a leading activist in the Burmese Women’s Union and the Network for Democracy and Development, based in exile.

It has been 22 years since 8.8.88, but the memory and spirit of that fateful day still lives on vividly in my heart, and the heart of so many activists inside and outside Burma.

It has been 22 years since 8.8.88, but the memory and spirit of that fateful day still lives on vividly in my heart, and the heart of so many activists inside and outside Burma.

Even to this day, I can remember adrenaline coursing through my body in anticipation of what we hoped would be the most significant demonstration in Burma to date.

This was the day we had planned for through covert underground organizing and reaching out to people from all segments of society—high school students, farmers, civil servants, workers, men, women, and many more. We had barely any resources at our disposal, no computers, no Internet, no mobile phones—nothing but our own belief, unity and commitment to bring about justice and truth.

Luckily, when the opportunity arose to have an interview with a BBC reporter Christopher Gunness, we were able to voice the call for a general strike on Aug. 8, 1988, to all the people of Burma.

The catalyst for the general strike was the death of a fellow student on March 13, 1988. Phone Maw came across a small student protest at the Rangoon Institute of Technology at the same moment riot police stormed the demonstration and opened fire indiscriminately. The authorities refused to allow his parents to reveal the truth about his death. The grieving parents were not even allowed to hold a funeral.

We were outraged and demanded that the authorities reveal the truth about their actions. By this time, the dire economic circumstances throughout Burma had struck at the heart of the general public, and catalyzed by the vigor of the student movement, people were ready for a public call for change.

On Aug. 7, 1988, after our final preparation meeting for 8.8.88, I returned home lost in my own thoughts, imagining and envisioning the demonstrations and all the people protesting on the streets, united in their desire for freedom and change.

As I entered the house, I heard my mother cry out, and saw my mother, two sisters and brother all waiting for me with frantic, concerned expressions.

Since I first joined my fellow students in the Red Bridge protest on March 16, which resulted in beatings and arrests, my family did not approve of my involvement in politics in fear of my personal safety.

So on the eve of the 8.8.88 protests, my family staged an intervention. They told me not to participate in the demonstrations, beseeching me to consider my mother’s concerns, asking if I would allow our mother to die from worrying about me getting shot and killed on the streets. My sisters asked me to lie to my mother to allay her fears and slip out early in the morning. But I knew I was doing the right thing in seeking justice and change for Burma, and I refused to compromise my values and lie to my family.

But no sooner had I declared my unwillingness to give in did my brother snap. He was a caring brother, but in that moment, that brotherly love compelled him to beat me in order to prevent me from joining the protests. He dragged me into his car and took me to his apartment in downtown Rangoon, only two blocks away from the City Hall and Sule Pagoda, the central meeting point for the demonstrations.

That night, I could not sleep. I was overwhelmed with despair and guilt for not being able to join in the historic event that I took part in organizing with my ’88 brothers such as Min Zeya, Htay Kywe, Ant Bwe Kyaw, Hla Myo Naung, who were all imprisoned after 1988. Their continued efforts calling for national reconciliation and democracy in the 8888 spirit after release from prison resulted in their second prison terms of 65 years following the Saffron Revolution.

Finally, the morning of 8.8.88 arrived. Looking down from my brother’s apartment balcony, I grew increasingly nervous. Would people support our call to join in the general strike? Would people come out to the streets to protest against the dictatorship?

Up until 9 a.m., the streets were quiet. But by 10 a.m., I started to see small groups forming on the street. Over the course of the day, I watched as the demonstrations expanded. Small groups became large gatherings, and gatherings became crowds.

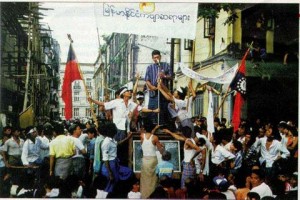

There was anxiety and hope written on the faces of the demonstrators—their anxiety of the unknown and fear of a crackdown mingled with their fervent aspirations for freedom. Waves of people filled the streets, bearing signs and flags with the fighting peacock, chanting, “Down with the one party system! Down with the military dictatorship!” in one strong, unified voice. I still feel chills every time I recall this memory.

Dusk fell and the chanting continued. Demonstrators gathered in front of city hall. The authorities aimed their loudspeakers at the demonstrators, shouting for them to disburse.

Although the protests were overwhelmingly promising and inspiring, I still had a sense that the army could carry out a brutal crackdown on the demonstrators. I kept crying and praying to Buddha that the day would end and come midnight, all would end peacefully.

My wish was not fulfilled. At approximately a quarter to midnight, armed policemen from the Kyauktada Police Station, located behind my brother’s apartment, marched into the streets. Within a minute, I could hear the clear, harrowing sound of gunfire and people’s screams and footsteps as they fled the scene. As the gunfire and screams died down, I heard trucks full of arrested protestors drive off, leaving only the sounds of the authorities securing the scene and declaring their might. I cried out loud. Some had predicted the shootings. Before he resigned, Gen. Ne Win declared, “guns will not shoot upwards.” Ne Win and his successor Brig-Gen. Sein Lwin kept their promise.

Aug. 8 ended in death and bloodshed but the momentum of the uprising increased, and I continued to work with my colleagues.

In the 90s, I shared my 8.8.88 experience with hundreds of supporters around the world during my advocacy trips to raise awareness about our struggle for democracy. However, for many years I have not been able talk about this experience again, inhibited by my own feelings of guilt for having yet to bring about democracy and freedom for our people, even after so many have sacrificed their lives on the streets, in the jungles and in prisons.

But I cannot just hold myself back. I need to move on. We need to move on from the tragedies towards positive action until we achieve democracy. We must learn from our past and honor and preserve the spirit of 8.8.88—the spirit of unity, sacrifice and setting aside differences of political beliefs and opinions—be they political beliefs, ideology, ethnicity, religion or gender.

From the 8.8.88 uprising, we were able to bring down a 26-year-old authoritarian regime because we were united as a country. It was so pure, that spirit of unity. We were able to transcend our differences for our common vision of justice and democracy for all. In 1988, the students and the general public mobilized as one to carry the flag of change around the nation. As the people passed the flag to the political leaders, some were not ready to hoist it up the flag post, since they were unable to overcome personal egos and differences of beliefs. The democracy relay was cut short because a lack of unity and discord led various groups to drop the baton.

8.8.88 sowed the seeds of change in the hearts of millions of people in Burma, and this seed will only continue to grow with each coming generation. But my greatest wish is for us to retain that same spirit of unity that captured the country’s imagination more than 22 years ago, as that cohesiveness is our only chance for genuine national reconciliation and democracy in Burma.

Our movement for democracy and ethnic equality is dynamic, diverse and vast, and we must cherish and respect the differences among us. But if we are not unified in our push for change, if we cling to our differences, or just rely on our own pride, then we do not need the military to divide us—we are already dividing ourselves.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi said, “Our differences should not be our weakness; our differences should be our strengths.” I hope we can echo her vision and bring an end to military rule with that same spirit of 8.8.88—Unity.

Article originally appeared in the Irrawaddy

Tags: 8888 Anniversary, Khin OhmarThis post is in: Blog

Related Posts(၂၇) ႏွစ္ေျမာက္ ရွစ္ေလးလုံးဒီမုိကေရစီ အေရးေတာ္ပုံေန႔ သေဘာထားထုတ္ျပန္ေၾကညာခ်က္

Rule of law still evades Myanmar 25 years after uprising

Statement of Endorsement for Declaration of 8888 Silver Jubilee

ရွစ္ေလးလုံး ဒီမိုုကေရစီ အေရးေတာ္ပံုု ေငြရတု ေၾကညာစာတမ္း

The Fallen Heroes and Heroines of 8888 Must Be Honored With Accountability

All posts

All posts