Burmese Media Spring

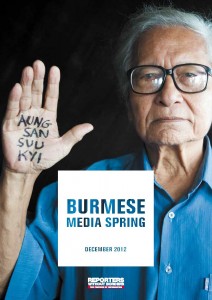

By Reporters Without Borders • December 30, 2012“A wind of freedom is blowing through the Burmese media.” You can see that just by looking at the Burmese weeklies displayed on the wooden table serving as a newsstand on a Rangoon street corner. Nobel peace laureate Aung San Suu Kyi’s face is on the front page of many news weeklies, often full-page. Covers like this would have been impossible to find just a year ago.

The international community is witnessing an unprecedented democratic transition in Burma after half a century of often very harsh military dictatorship, during which the army turned its guns on the people on more than one occasion and crushed a “Saffron Revolution” by Buddhist monks in 2007.

Under pressure from the international community and from opposition groups backed by the population, the military government was forced to pursue the reforms announced in its “roadmap to democracy ” in 2003 and to hold general elections in 2010 that concluded with the installation of a civilian government.

Renamed Myanmar by the military, Burma is now being led down the road to democracy by Thein Sein, a former general who has been president since February 2011. The destination is still distant, but the road already covered is remarkable. Aung San Suu Kyi’s visits to Europe and the United States have been striking evidence of that.

For 25 years, Reporters Without Borders was banned from visiting Burma. All freely-reported news and information were forbidden and the country’s leading journalists were detained in its 43 jails. For years, the military regime would suspend publications for such trivial reasons as a St. Valentine’s Day advertisement or a reference to Thailand by the ancient name of Yodaya.

The repression spared no one involved in news production, not even printers, some of whom were sentenced to seven years in prison for printing poems with democratic messages. The arbitrary convictions and sentences continued until 2011, even after the first political reforms had begun. In October 2011, amnesty was decreed for dozens of political prisoners including the blogger and comedian Zarganar, Myanmar Nation editor Sein Win Maung and three Democratic Voice of Burma reporters.

After being removed from the blacklist at the end of August 2012, at the same time as Aung San Suu Kyi’s children and former US secretary of state Madeleine Albright, Reporters Without Borders was finally able to visit Burma for the first time and meet all the generations of journalists it had supported from a distance, including the wellknown Win Tin, who spent 19 years in prison, and those who had been on Democratic Voice of Burma’s list of imprisoned “VJs ” (video-journalists).

Reporters Without Borders was able to see the initial results of the measures designed to loosen the government’s grip on the media. But the way forward for the media is far from clear at this early stage of the government’s reforms. How do the media envisage the political and legal process leading to liberalization? Are journalists managing to convey their concerns, questions and, above all, their wishes to those in charge of these reforms ? What are the main challenges for the media in this new political

and economic configuration?

This report examines the state of the changes carried out by the government and offers detailed recommendations designed to improve respect for freedom of information in Burma and ensure that the improvements are lasting.

Tags: Freedom of Expression, Media Freedom, Reporters Without BordersThis post is in: Human Rights, Resistance, Spotlight

Related PostsMyanmar: Release Rakhine Rights-Defender Khaing Myo Htun

Burma: Dismantle Infrastructure of Repression

Statement on TWO’s Cancelled Press Conference

Film Censorship in Burma Underlines Existing Limits on Freedom of Expression

Myanmar: Release Four “Rohingya Calendar” Political Prisoners

All posts

All posts