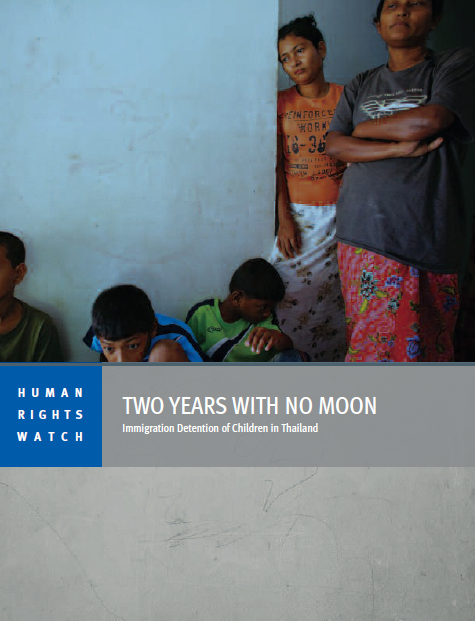

Two Years With No Moon: Immigration Detention of Children in Thailand

By Human Rights Watch • September 4, 2014Every year, Thailand arbitrarily detains thousands of children, from infants and toddlers and older, in squalid immigration facilities and police lock-ups. Around 100 children—primarily from countries that do not border Thailand—may be held for months or years. Thousands more children—from Thailand’s neighboring countries—spend less time in this abusive system because Thailand summarily deports them and their families to their home countries relatively quickly. For them, detention tends to last only days or weeks.

But no matter how long the period of detention, these facilities are no place for children.

Drawing on more than 100 interviews, including with 41 migrant children, documenting conditions for refugees and other migrants in Thailand, this report focuses on how the Thai government fails to uphold migrants’ rights, describing the needless suffering and permanent harm that children experience in immigration detention. It examines the abusive conditions children endure in detention centers, particularly in the Bangkok Immigration Detention Center (IDC), one of the most heavily used facilities in Thailand.

This report shows that Thailand indefinitely detains children due to their own immigration status or that of their parents. Thailand’s use of immigration detention violates children’s rights, immediately risks their health and wellbeing, and imperils their development. Wretched conditions place children in filthy, overcrowded cells without adequate nutrition, education, or exercise space. Prolonged detention deprives children of the capacity to mentally and physically grow and thrive.

In 2013, the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the body of independent experts charged with interpreting the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which Thailand is party, directed governments to “expeditiously and completely cease the detention of children on the basis of their immigration status,” asserting that such detention is never in the child’s best interest.

Immigration detention in Thailand violates the rights of both adults and children. Migrants are often detained indefinitely; they lack reliable mechanisms to appeal their deprivation of liberty; and information about the duration of their detention is often not released to members of their family. Such indefinite detention without recourse to judicial review amounts to arbitrary detention prohibited under international law.

Thailand requires many of those detained to pay their own costs of repatriation and leaves them to languish indefinitely in what are effectively debtors’ prisons until those payments can be made. Refugee families face the unimaginable choice of remaining locked up indefinitely with their children, waiting for the slim chance of resettlement in a third country, or paying for their own return to a country where they fear persecution. Many refugees spend years in detention.

Immigration detention, particularly when arbitrary or indefinite, can be brutal for even resilient adults. But the potential mental and physical damage to children, who are still growing, is particularly great.

Immigration detention negatively impacts children’s mental health by exacerbating previous traumas (such as those experienced by children fleeing repression in their home country) and contributing to lasting depression and anxiety. Without adequate education or stimulation, children’s social and intellectual development is stymied. None of the children Human Rights Watch interviewed in Thailand received a formal education in detention. Cindy Y., for example, was three years older than her classmates in school when she was finally released. She said, “I feel ashamed that I’m the oldest and studying with the younger ones.”

Detention also imperils children’s physical health. Children held in Thailand’s immigration detention facilities rarely get the nutrition or physical exercise they need. Children are crammed into packed cells, with limited or no access to space for recreation. Doug Y. wanted to play football, his favorite sport, but said, “If you kick a ball, you’d hit someone, or a little kid.” Parents described having to pay exorbitant prices for supplemental food smuggled from outside sources to try to provide for their children’s nutritional needs. Labaan T., a Somali refugee detained with his 3-year-old son, said, “The diet for the boy consists of the same rice that everybody else eats. He needs fruits which are neither provided nor available for purchase.”

The bare and brutal existence for children in detention is exacerbated by the squalid conditions. Leander P., an adult American who was detained in the Bangkok IDC, said that one of the two available toilets in his cell, occupied by around 80 people, was permanently clogged, so “someone had drilled a hole in the side – what would have gone down just drained onto the floor.” Multiple children we interviewed described cells so crowded they had to sleep sitting up.

Even where children have room to lie down and sleep, they routinely reported sleeping on tile or wood floors, without mattresses or blankets. “The floor was made from wood, the wood was broken and the water came in,” said one refugee woman detained for months in the Chiang Mai IDC with a friend and the friend’s 6 and 8 year-olds. “While I was sleeping, a rat bit my face.”

Severe overcrowding appears to be a chronic problem in many of Thailand’s immigration detention centers. The Thai government detained hundreds of ethnic Rohingya refugees, including unaccompanied children, in the Phang Nga IDC in 2013. Television footage showed nearly 300 men and boys detained in two cells resembling large cages, each designed to hold only 15 men, with barely enough room to sit. Eight Rohingya men died from illness while detained in extreme heat with lack of medical care in the immigration

detention centers that year.

Children are routinely held with unrelated adults in violation of international law, where they are exposed to violence between those detained and from guards. A Sri Lankan refugee, Arpana B., was pregnant and detained in an overcrowded cell in the Bangkok IDC with her small daughter in 2011. “One of the detainees beat my daughter,” she said. “He was crazy. There was no guard, no police to help us.”

Thailand faces numerous migration challenges posed by its geographical location and relative wealth, and is entitled to control its borders. But it should do so in a way that upholds basic human rights, including the right to freedom from arbitrary detention, the right to family unity, and international minimum standards for conditions of detention. Instead, Thailand’s current policies violate its international legal obligations, put children at unnecessary risk, and ignore widely held medical opinion about the detrimental effect that detention can have on the still-developing bodies and minds of children.

Alternatives to detention exist and are used effectively in other countries, such as open reception centers and conditional release programs. Such programs are a cheaper option, respect children’s rights, and protect their future. The Philippines, for instance, operates a conditional release system through which refugees and other vulnerable migrants are issued with documentation and required to register periodically.

Children should not be forced to lose parts of their childhood in immigration detention. Given the serious risks of permanent harm from depriving children of liberty, Thailand should immediately cease detention of children for reasons of their immigration status.

Download the full report here.

Tags: Children, Convention on the Rights of the Child, Human Rights Violations, Human Rights Watch, Human Trafficking, International Organization for Migration, Migrant Workers, Muslims, National Council for Peace and Order, Refugees, Rohingya, Thailand, UNHCRThis post is in: Children and Youth, Human Rights, Spotlight

Related PostsJSMK Update: Treating More than One Problem

Five Years of War: A Call for Peace, Justice, and Accountability in Myanmar

One in Five Children in Myanmar Go to Work Instead of Going to School, New Census Report Reveals

In Flood-Affected Rural Areas, Poorest People Face Highest Food Insecurity Risk And Livestock And Fisheries Sectors Yet To Recover From Severe Damage

ကခ်င္အမ်ိဳးသမီးမ်ားအစည္းအရံုးထိုင္းႏိုင္ငံ (KWAT) မွကခ်င္ျပည္နယ္အတြင္း ျမန္မာစစ္အစိုးရႏွင့္ ကခ်င္လြတ္ေျမာက္ေရးတပ္မေတာ္တို႔ ၏စစ္ျပန္လည္္ျဖစ္ပြားမႈ၄ႏွစ္ျပည့္ႏွင့္ပတ္သက္ျပီးထုတ္ျပန္ခ်က္

All posts

All posts