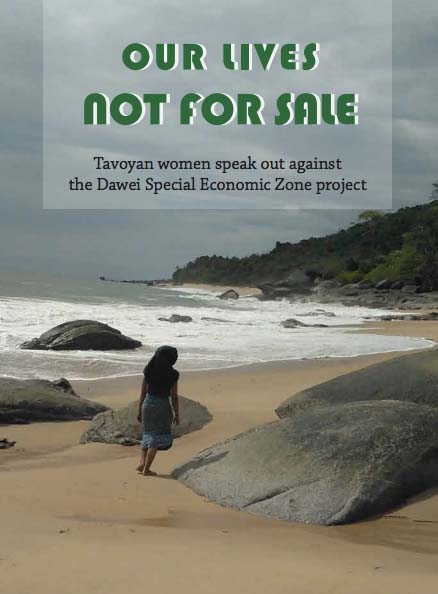

Our Lives Not For Sale: Tavoyan Women Speak Out Against the Dawei Special Economic Zone Project

By Tavoyan Women's Union • December 23, 2014 This report exposes the damaging impacts of the Dawei Special Economic Zone (DSEZ) project on rural Tavoyan women living in six affected villages in southern Burma.

This report exposes the damaging impacts of the Dawei Special Economic Zone (DSEZ) project on rural Tavoyan women living in six affected villages in southern Burma.

Most of the local population are fisherfolk and farmers, who have lived sustainably for generations in this isolated coastal area. They have been given no choice about accepting this multi-billion dollor Thailand-Burma joint venture, which will turn their pristine lands into the largest petrochemical estate in Southeast Asia.

Despite delays and funding constraints since implementation began in 2010, the project has been progressing steadily on the ground. Most of the coastal area near the project has been turned into a no-go zone, and large areas of farmland confiscated and destroyed to build initial infrastructure.

TWU conducted interviews with 60 women, chosen randomly from six villages in Htein Gyi tract, where the deep sea port is being built. Findings from these interviews show that the project has already been extremely damaging to the livelihoods of local communities:

• Almost all the women have suffered loss of income since the project began, due to land confiscation, destruction of farmlands, and restricted access to the coast. Just over a third of the women now have no income at all from their former livelihoods.

• About half of the women had suffered land confiscation, but only a third of them said that their families had received compensation. Amounts of compensation were uneven, and as low as 500,000 kyat per acre (US$500), for land which could yield an annual income of over one million kyat (US$1,000).

• Whereas families were previously able to live comfortably off income from their farms and other livelihoods, they are now facing food insecurity, and can no longer afford to send their children to school. 49 of the women said they had taken their Executive Summary Our Lives – Not for Sale i children out of school since the project began; a third of these women had taken children under 13 out of school.

The interviews also highlighted specific vulnerabilities of women related to the project, mostly due to traditional gender discrimination:

• While there has been very little information provided about the project to local communities, women have received even less information about the project than men. It was mainly men who attended meetings held about the project; some women only learned about the project when bulldozers began clearing their lands.

• Women have been excluded from decision making over land sale and compensation, as men’s names are automatically listed on land documents as household heads. Among 60 women, only two were listed as the users of their land, as their husbands had died. Compensation was therefore usually paid into the hands of men, giving them sole discretion about spending. In cases where women were listed as land users, they were vulnerable to bullying by male authorities to give up rights to their land. All the village administrative officers in this area are men.

• Livelihoods carried out specifically by women have been drastically affected by the project. Shellfish collection along the seashore is a traditional source of income for women, but now is severely restricted due to blockage of access to the coast.

• There has been sexual harassment by project workers of local women, making it unsafe to go out foraging for food in the vicinity of the project.

• Due to food insecurity as a result of the project, girls are increasingly being sent to work in Thailand to earn money to send back to their parents. This is regarded as a duty for daughters rather than sons, due to the gendered expectation that girls are caregivers in the family. Girls under 18 must travel illegally to Thailand, placing them at risk of trafficking, exploitation and abuse.

• Due to the low priority placed on educating girls, most women have very low levels of education, and fear they will have no means of survival when they are resettled away from their lands to make way for the project. They have no hope of finding jobs in the DSEZ, where only educated or skilled workers are expected to be hired. Over two-thirds of the women interviewed had only completed primary education. Seven were illiterate.

Despite the clear vulnerability of women related to the project, there has been no attempt by the project developers to identify or address these problems. The Burmese government is obligated under the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) to ensure that rural women can participate in and benefit from development projects, but has implemented no mechanisms to ensure this. The new Myanmar Special Economic Zone Law, issued in January 2014, makes no mention of women whatsoever.

TWU has been opposed to the DSEZ from the outset, due to the complete lack of transparency and exclusion of local communities from decision-making around the project, and due to the large-scale social and environmental damage it will cause. We have visited Thailand’s Map Ta Phut industrial estate and seen firsthand how the dangerous levels of pollution have devastated local farming, fishing and tourism livelihoods and caused high rates of cancer among local communities. We are determined not to accept a similar project in our homelands.

Local women have started to take action against the DSEZ and related projects. They have held public protests, and in a village ii Tavoyan women speak out against the Dawei Special Economic Zone projectouth of Dawei, have led their community to block Chinese and Burmese military developers from proceeding with a planned oil refinery linked to the DSEZ project.

TWU stands in strong solidarity with these brave women, and makes the following demands: To the Burmese and Thai governments, and to the project developers:

• Immediately stop the DSEZ project.

• Return any lands which have been confiscated to their original owners.

• Provide proper compensation to those whose lands have been confiscated or whose crops or farmlands have been damaged by the project.

• Stop restricting access to the coastal area

• Allow all roads built for the project to be used freely by the public.

• Hand over buildings constructed at the project site to local communities, to be used for the benefit of the public

• Dismantle the small port already built for the project, as the dock is too high to be used by local people’s fishing boats

To the Burmese government:

• There should be constitutional reform to establish a federal system of government, in which decision making power over large-scale development projects such as the DSEZ is devolved down to the state and regional level.

• For any future large development projects in the Dawei area, ensure that there is Free Prior and Informed Consent of local communities, with equal participation of women. There must be transparent Environmental Impact Assessments, Social Impact Assessments and Health Impact Assessments conducted before the project.

• In compliance with CEDAW, review existing laws related to rural development, to ensure the protection of rural women’s rights.

This post is in: Displacement, Economy, Human Rights, Women

Related PostsLand Policies and Laws Must Reflect Rights and Interests of Vulnerable Communities

Yearning to be Heard: Mon Farmers’ Continued Struggle for Acknowledgement and Protection of their Rights

WORLD REPORT 2015

A Briefing by Burmese Rohingya Organization UK: International Investigation Urgently Needed into Human Rights Abuses Against the Rohingya

Burma: Stop Christian cross Removal; Drop Trumped-up Charges

All posts

All posts