Spotlight (188 found)

What Refugees Say…

Between March‐April this year, focus group discussions were held with temporary returnees to SE Burma/ Myanmar from all 9 refugee camps along the Thailand‐Burma/ Myanmar border. The aim was to gain a snapshot of individual perspectives and concerns on current conditions on the ground, rather than conducting a formal survey representational of the whole refugee caseload.

The consultations focused on the conditions in the areas they returned to, the changes they and residents in those areas had detected since recent political and military shifts in the country, and their perceived current barriers to return.

The participants were identified by Section Leaders, with criteria that they must have returned to SE Burma/ Myanmar since the ceasefires were brokered, be adults, and that there should be some gender equity amongst them. In total, 85 temporary returnees participated in the consultations, with 35% being female. Over 100 others, comprising senior community leaders and CBO staff were also engaged through the process, although the main findings in this report only reflect the perspectives of those who had recently returned to their country of origin […]

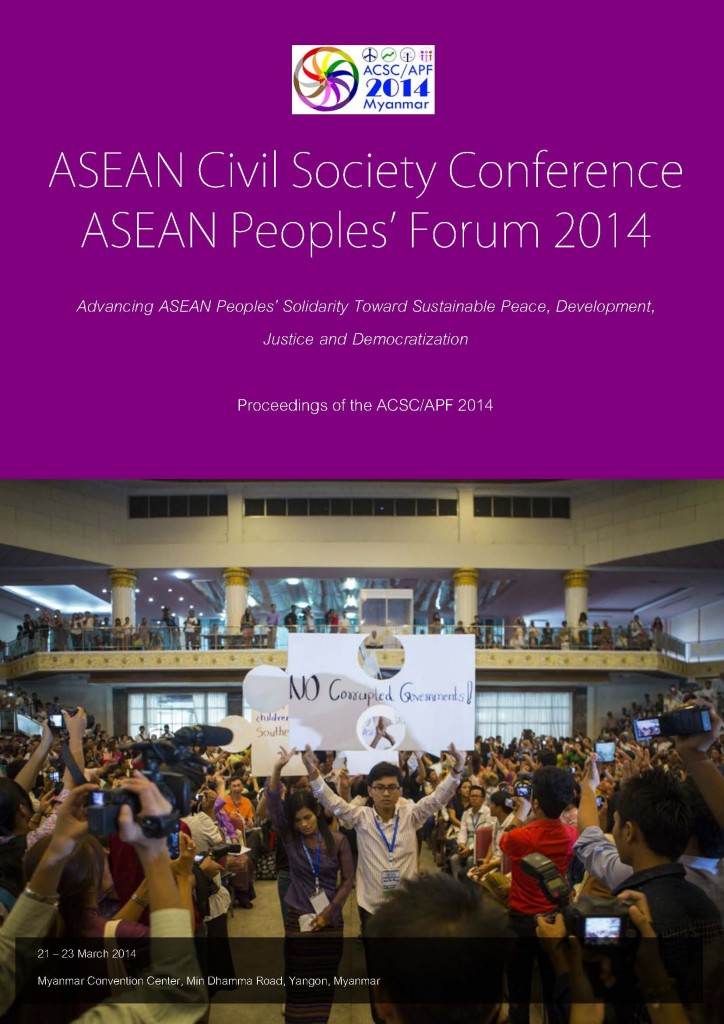

• • •ACSC/APF 2014 Post Conference Report

As a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Myanmar accepted the gavel that symbolizes the ASEAN presidency. This was a historic moment since this is the first time Myanmar has taken the Chair since it became a member of ASEAN. As Chair, Myanmar is responsible for hosting many important regional forums and events during 2014.

The ASEAN Civil Society Conference (ACSC), also known as the ASEAN Peoples’ Forum (APF), is held independently by the ASEAN Chair country in advance of, and parallel to, the official ASEAN Summit, which is attended by ASEAN and regional leaders. The first ACSC/APF took place in Malaysia in 2005. Since then it has taken place in the Philippines (2006), Singapore (2007), Thailand (2009), Vietnam (2010), Indonesia (2011), Cambodia (2012), Brunei (2013) and this year in Myanmar (2014). The 10th ACSC/APF took place on 21 – 23 March 2014 at the Myanmar Convention Center in Yangon, Myanmar.

• • •Navigating Paths to Justice in Myanmar’s Transition

Since President Thein Sein and his government took office in 2011, Myanmar’s transition has unfolded at a pace that has surprised many and earned the acclaim of western governments, financial institutions, and private-sector investment analysts.1 The Burmese population of approximately 60 million has endured more than a half-century of military dictatorship, armed conflict, economic dysfunction, and political repression.2 A meaningful transformation into a peaceful society that enjoys economic development and functions democratically now seems plausible, though it is far from guaranteed. Ultimately, the blanket immunity afforded by the 2008 Constitution shields the acts attributable to prior regimes from any form of accountability.3 Whether the reform process will evolve to include measures that address the massive and systematic injustices of the past remains less certain.

• • •In Pursuit of Justice: Reflections on the Past and Hopes for the Future of Burma

Since 2011, Burma has begun to emerge from 50 dark years of dictatorship. Now, under President Thein Sein’s nominally civilian government the possibility has arisen for Burma to begin rebuilding and reconciling divided segments of the nation, and to provide justice to victims for decades of human rights abuses.

Burma’s minority ethnic communities have experienced grave human rights abuse at the hands of the SPDC regime and its strong arm of the Burmese military, or Tatmadaw. In order to transition successfully towards true democracy and national reconciliation, the Burmese government must address, and act upon, the specific needs expressed by victims of past abuse, documented and expounded herein, in order to move away from the abusive culture of the past towards a united future.

Within this report you will find a detailed history of Burma’ ethnic conflict, how that conflict has been sewn into the very fabric of the SPDC regime’s ideology and governing strategy, and ways in which the Tatmadaw has implemented the regime’s strategy by crippling livelihoods, physically and mentally abusing, and destroying the security of Burma’s minority ethnic communities […]

• • •Myanmar: End Wartime Torture in Kachin State and Northern Shan State

(Yangon)— For the past three years, Myanmar authorities have systematically tortured Kachin civilians perceived to be aligned with the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), Fortify Rights said in a new report released today. Fortify Rights believes these abuses constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity. The government of Myanmar should intervene immediately to end the use of torture in the conduct of the ongoing war in Kachin State and northern Shan State, and it should credibly investigate and prosecute members of the Myanmar Army, Myanmar Police Force, and Military Intelligence who are responsible for the serious crimes described in this report.

(Yangon)— For the past three years, Myanmar authorities have systematically tortured Kachin civilians perceived to be aligned with the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), Fortify Rights said in a new report released today. Fortify Rights believes these abuses constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity. The government of Myanmar should intervene immediately to end the use of torture in the conduct of the ongoing war in Kachin State and northern Shan State, and it should credibly investigate and prosecute members of the Myanmar Army, Myanmar Police Force, and Military Intelligence who are responsible for the serious crimes described in this report.

The 71-page report, “I Thought They Would Kill Me”: Ending Wartime Torture in Northern Myanmar, describes the systematic use of torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment or punishment (“ill treatment”) of more than 60 civilians by Myanmar authorities from June 2011 to April 2014. Members of the Myanmar Army, Myanmar Police Force, and Military Intelligence deliberately caused severe and lasting mental and physical pain to civilians in combat zones, […]

• • •Truce or Transition? Trends in Human Rights Abuse and Local Response in Southeast Myanmar Since the 2012 Ceasefire

In January 2012, the Myanmar government and the Karen National Union (KNU) signed a preliminary ceasefire agreement, bringing to a halt what is often referred to as the world’s longest-running civil war. This conflict engendered severe human rights abuse of civilians at the hands of a range of armed actors, primarily at those of the Myanmar Armed Forces (Tatmadaw). The ceasefire and other recent political developments in Myanmar have altered the ways in which human rights abuse is experienced by Karen people in the Southeast, and transformed the context within which these abuses can be addressed. This report aims to demonstrate how trends in human rights abuse have changed during the post-ceasefire period […]

• • •Same Impunity, Same Pattern: Sexual Abuses by the Burma Army Will Not Stop Until There is a Genuine Civilian Government

Almost a decade ago, the Women’s League of Burma (WLB) denounced systematic patterns of sexual crimes committed by the Burma Army against ethnic women and demanded an end to the prevailing system of impunity. Today WLB is renewing these calls. Three years after a nominally civilian government came to power; state-sponsored sexual violence continues to threaten the lives of women in Burma.

Almost a decade ago, the Women’s League of Burma (WLB) denounced systematic patterns of sexual crimes committed by the Burma Army against ethnic women and demanded an end to the prevailing system of impunity. Today WLB is renewing these calls. Three years after a nominally civilian government came to power; state-sponsored sexual violence continues to threaten the lives of women in Burma.

Women of Burma endure a broad range of violations; this report focuses on sexual violence, as the most gendered crime. WLB and its member organizations have gathered documentation showing that over 100 women have been raped by the Burma Army since the elections of 2010. Due to restrictions on human rights documentation, WLB believes these are only a fraction of the actual abuses taking place […]

Training War Criminals? – British Training of the Burmese Army

This briefing examines the British government’s controversial military training to the Burmese Army.

The training is taking place despite the Burmese Army still committing serious human rights abuses which violate international law. Crimes committed by the Burmese Army since the reform process began include rape and gang rape of ethnic women, including children, deliberate targeting of civilians, arbitrary execution, arbitrary detention, torture, mutilations, looting, bombing civilian areas, blocking humanitarian assistance, destruction of property, and extortion. Many of these abuses could be classified as war crimes and crimes against humanity […]

• • •Ethnic Conflict in Burma/Myanmar: From Aspirations to Solutions

In November, TNI/BCN hosted a two-day seminar, involving ethnic groups from different regions of Burma, on the theme of “Ethnic Conflict in Burma/Myanmar: From Aspirations to Solutions”. Those participating included 20 representatives from Burmese civil society, political and armed opposition groups.

The seminar focused on four main areas: political reform; moving from ceasefires to political dialogue; land rights and natural resource extraction; and ethnic identity and citizenship […]

• • •Not a Rubber Stamp: Myanmar’s Legislature in a Time of Transition

Myanmar’s new legislature, the Union Assembly formed in 2011 on the basis of elections the previous year, has turned out to be far more vibrant and influential than expected. Both its lower and upper houses have a key role in driving the transition process through the enactment and amendment of legislation needed to reform the outdated legal code and are acting as a real check on the power of the executive.

Yet, some bills moving through the legislature have raised concerns that the authorities, both legislative and executive, may not be ready to give up authoritarian controls on the media, on civil society organisations and on the right to demonstrate. More broadly, the role of the 25 per cent military bloc and its impact on the legislature have been questioned. Serious individual and institutional capacity constraints and unclear procedures serve as a brake on effective, efficient lawmaking […]

• • •

All posts

All posts