Posts Tagged ‘Article 436’ (7 found)

Burma – Where Classrooms are replaced with Jail Cells

On 2 July 2015, five student protestors were charged under the controversial Peaceful Assembly and Procession Law for taking part in a protest concerning the overpowering influence of the Burma Army in Parliament. An additional four students were arrested after being involved in a graffiti protest on the campus of Yadanabon University in Mandalay. The demonstrations came as a result of the ongoing detention and subsequent unfair trials of students protesting the national education law along with the failure of Parliament to pass five out of six proposed amendments to the 2008 Constitution, most notably Article 436 […]

On 2 July 2015, five student protestors were charged under the controversial Peaceful Assembly and Procession Law for taking part in a protest concerning the overpowering influence of the Burma Army in Parliament. An additional four students were arrested after being involved in a graffiti protest on the campus of Yadanabon University in Mandalay. The demonstrations came as a result of the ongoing detention and subsequent unfair trials of students protesting the national education law along with the failure of Parliament to pass five out of six proposed amendments to the 2008 Constitution, most notably Article 436 […]

Constitutional Crackdown Brings A Dark Day for Democracy in Burma

After an increasingly dispiriting start to 2015, and with landmark national elections now likely only five months away, Burma’s flimsy “reform process” is unraveling inexorably. First there was the 10 March crackdown on the nationwide student protest movement at Letpadan, Bago Region; then the Committee to Protect Journalists’ revealed that, despite much-heralded media reforms in 2011, Burma featured yet again in its 2015 rogues’ gallery of top 10 most censored countries on the planet; more recently, the refugee crisis, triggered mostly by severe state and religious persecution of the Rohingya and other Muslim minorities in Arakan State, caught the world’s attention. Meanwhile, grave human rights abuses – including sexual violence – continue unabated in ethnic conflict areas, especially in war-torn Kachin State, parts of northern Shan State and Arakan State, bringing the total number of IDPs in Burma to over 660,000.

After an increasingly dispiriting start to 2015, and with landmark national elections now likely only five months away, Burma’s flimsy “reform process” is unraveling inexorably. First there was the 10 March crackdown on the nationwide student protest movement at Letpadan, Bago Region; then the Committee to Protect Journalists’ revealed that, despite much-heralded media reforms in 2011, Burma featured yet again in its 2015 rogues’ gallery of top 10 most censored countries on the planet; more recently, the refugee crisis, triggered mostly by severe state and religious persecution of the Rohingya and other Muslim minorities in Arakan State, caught the world’s attention. Meanwhile, grave human rights abuses – including sexual violence – continue unabated in ethnic conflict areas, especially in war-torn Kachin State, parts of northern Shan State and Arakan State, bringing the total number of IDPs in Burma to over 660,000.

WORLD REPORT 2015

Burma

The reform process in Burma experienced significant slowdowns and in some cases reversals of basic freedoms and democratic progress in 2014. The government continued to pass laws with significant human rights limitations, failed to address calls for constitutional reform ahead of the 2015 elections, and increased arrests of peaceful critics, including land protesters and journalists […]

• • •Political Opposition in Burma Must Ignore Distractions and Focus on Policy

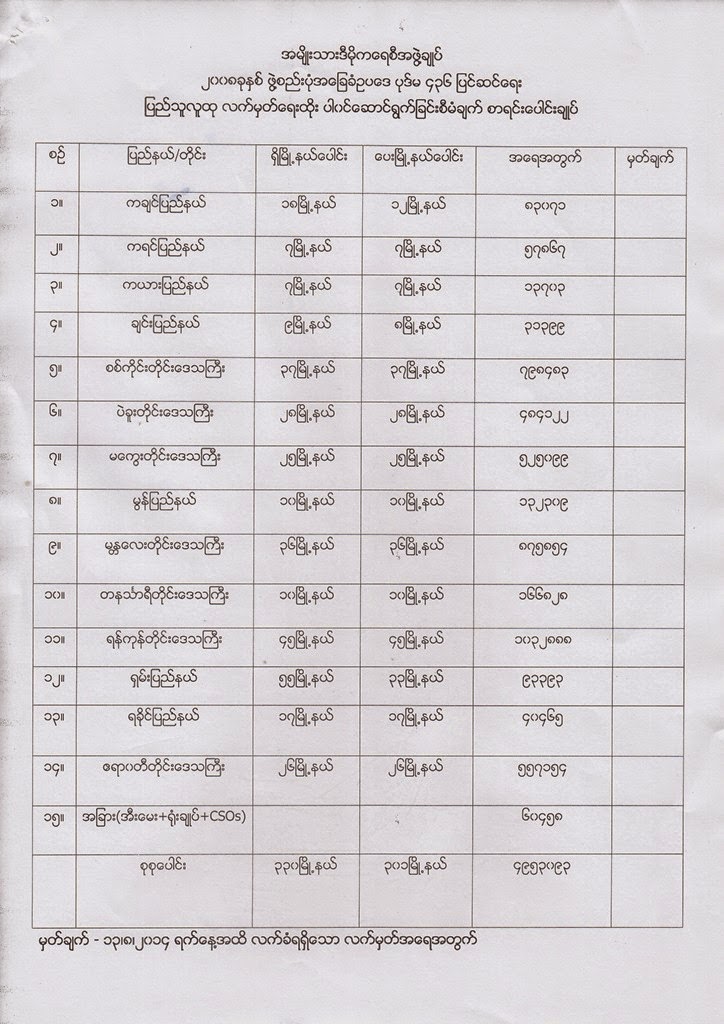

The main opposition party in Burma, the National League for Democracy (NLD), said last week that almost 5 million people signed the petition calling for constitutional reform that did the rounds from 27 May to 19 July. The petition pushed for the removal of the Burma Army’s veto on constitutional change that they have by virtue of Article 436 of the Burma Constitution. This campaign has been widely praised as a shrewd tactical move, because it would in theory unlock the door to amendments of any offending articles of the Burma Constitution that undermine democratic values and infringe upon the fundamental rights of the people. Most notably – though by no means exclusively, as the NLD and others are at pains to stress – amendment of Article 436 will in turn enable amendment of Article 59(f), which in practice bars Daw Aung San Suu Kyi running for President in the 2015 elections.

The main opposition party in Burma, the National League for Democracy (NLD), said last week that almost 5 million people signed the petition calling for constitutional reform that did the rounds from 27 May to 19 July. The petition pushed for the removal of the Burma Army’s veto on constitutional change that they have by virtue of Article 436 of the Burma Constitution. This campaign has been widely praised as a shrewd tactical move, because it would in theory unlock the door to amendments of any offending articles of the Burma Constitution that undermine democratic values and infringe upon the fundamental rights of the people. Most notably – though by no means exclusively, as the NLD and others are at pains to stress – amendment of Article 436 will in turn enable amendment of Article 59(f), which in practice bars Daw Aung San Suu Kyi running for President in the 2015 elections.

While such a public initiative is to be applauded, and the weight of support for the petition is to be welcomed, the political opposition in Burma must not allow itself to be distracted by such diversionary machinations on the part of the Burma Government and the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP). The NLD is right that constitutional reform is essential to the establishment of genuine democracy in Burma. However, it is also time for the political opposition to test the limited democratic space that now exists in Burma, and time to start outlining a viable policy platform for government. The burden rests with the NLD and other democratic opposition parties to engineer a seismic cultural and political shift: away from politics traditionally centred on personalities and fear, and towards politics based on actual policies that will resolve people’s grievances and promote and protect their political, economic, social and cultural rights.

• • •Burma Must Amend the 2008 Constitution for the Reform to be Genuinely Democratic

The National League for Democracy (NLD) and its leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, have faced intimidation from Burma’s electoral commission in recent weeks as the campaign to amend Burma’s 2008 Constitution continues to draw strong support throughout the country. As the public rallies behind the campaign, Burma’s ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) have accused the campaign leaders of sowing public unrest and disorder.

The National League for Democracy (NLD) and its leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, have faced intimidation from Burma’s electoral commission in recent weeks as the campaign to amend Burma’s 2008 Constitution continues to draw strong support throughout the country. As the public rallies behind the campaign, Burma’s ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) have accused the campaign leaders of sowing public unrest and disorder.

Last month, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi spoke to a crowd of over 20,000 supporters in Mandalay, calling on the military to forgo their fear of constitutional amendment in support of democratic reform. According to a recent statement from Human Rights Watch, the Union Electoral Commission (UEC) subsequently warned the NLD leader that such comments are illegal and unconstitutional, and could jeopardize her party’s re-registration ahead of by-elections in 2014. The NLD has responded to the UEC’s warning as inappropriate, owing to the fact that political parties are allowed to stage rallies so long as they are in accordance with the law.

• • •Burma: Election Body Intimidating Opposition

Burma’s electoral commission should immediately cease threatening and intimidating the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) party, Human Rights Watch said. The electoral commission should also drop proposals that would set limits on future election campaigning, and President Thein Sein and the Burmese government should publicly reject such proposals […]

• • •

All posts

All posts